The relation between philosophy and history of philosophy is controversial. Some believe that history is of mere instrumental value; reading the odd classic might prevent us from reinventing the wheel and sharpen our wits. Others believe that history is an integral part of philosophy; working through our ancestors is necessary of finding our own place. Let’s call them the instrumentalists and the integralists. Of course, there are good reasons for both views. Although I have slight leanings towards the latter view, I don’t want to argue for it. Rather, I wonder whether even instrumentalists engage in some sort of history when they practise philosophy without any obvious historical ties. What, you might ask, is the point of showing such a thing? Well, I think that all camps, historians and philosophers, no matter whether they are instrumentalists or integralists, can learn from one another. So my point is not that philosophy is inherently historical; my point is that doing philosophy involves doing (some) history.

Now how does philosophy involve history? I think a very basic issue that any philosopher will have addressed (at least tacitly) is the question of why a certain problem arises in the first place. Imagine someone claims that p. If you think or want to argue that not-p, you must have some idea why you find p problematic. It doesn’t matter whether “p” = “all humans are equal” or “the mind is like a computer.” Any claim needs justification, and if you want to offer such a justification you will need to begin with an understanding of what precisely needs justifying. This means you need some understanding of why a certain problem arises for you or for certain participants in a debate. Now the point is that the question of why a problem arises is always sensitive to a certain context, no matter whether you ask why a problem arises for you or your contemporaries or for Spinoza. History doesn’t need to be about dead people; it can be about you, too.

But why, you might ask, does that matter? Certain problems just never go away, do they? That problems arise is, you might say, a fact about certain concepts or their application, not about your personal take on the matter. At this point, philosophers often invoke the distinction between the context of justification and context of discovery. It doesn’t matter whether you discovered your dislike for Fodor’s computational theory of mind while having a shower or during a walk to the pub. Justification is one thing; the history of a justification or a problem is another.

But my point is not that certain biographical details might lead to the discovery of a problem; the issue is why a problem or a certain set of concepts is relevant. In other words, the question is why something is a problem. When you spell out why a problem arises for you, you won’t tell me the story of your life but you will appeal to facts about concepts: your rejection of Fodor’s theory will perhaps rely on the concept of computation. But such facts about concepts are (partly) historical facts, unless you want to claim that Hobbes and Fodor use “computational” in the same sense. Historical facts about our understanding and the relevance of concepts and problems are not external to our current debates. They determine whether we find certain intuitions relevant, whether we speak about the same thing or past one another. Of course, we often don’t take notice why things matter to us, but once we leave the boundaries of our specialisations or the field of philosophy we are reminded quickly of our synchronic anachronisms. This is why context is tied up with relevance. Thus, the answer to the question of why a problem arises remains unsaturated so long as we don’t spell out why it is relevant to whom.

That said, there are also crucial differences between philosophy and its history. While certain philosophers stress that they are interested in making true claims, historians will point out that they are also interested in why certain claims stick around. Facts that make a claim true are (often) different from what makes the claim stick in our minds and debates. But the question why something matters to us involves both kinds of facts. This is why philosophy is always history, to some extent of course.

This piece is shared with permission from Martin Lenz. It was originally published on Martin’s blog, Handling Ideas.

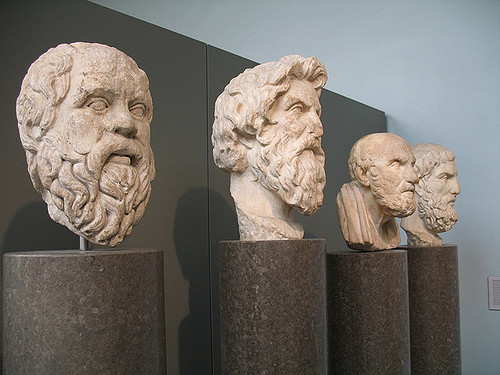

Photo by J.D. Falk.

Martin Lenz

Martin Lenz (@Going_Loopy) is professor and department chair in history of philosophy at Groningen University. He specialises in medieval and early modern philosophy. Before joining the philosophy faculty at Groningen in 2012, Martin studied Philosophy, Linguistics and German Literature in Bochum, Budapest and Hull (M.A. in 1996; PhD in 2001 in Bochum) and spent his postdoctoral period in Cambridge, Tübingen and Berlin (Habilitation in 2009).